Many persons think that you can't get a patent on a perpetual motion machine. That's not true, as these examples show.

|

| George Linton (1821) British Patent 4632 Dircks (1861) p. 436 |

|---|

|

| The bucket brigade engine Br. Patent No. 1330 Dircks (1861) p. 478 |

|---|

The apparatus is composed of a number of hollow elastic buckets or bellows, partly immersed in water, made to pass over two pulleys. Each bellows is furnished with leaden weights at the bottom, which forces the air contained in the bellows on one side, to pass by means of connecting tubes into those buckets or bellows that are on the opposite side. The bellows are fitted to slotted links, and connected together so as to form an endless chain, which passes over the two pulleys.

|

| Pierre Richard (engineer, Paris), 1858, British patent No. 1870. Dircks (1861), p. 482. |

|---|

|

|

| Top view. | Side view. |

|---|---|

| Johann Ernst Friedrich Lüdeke (1864), Dircks (1870), p. 239 | |

|

| Rebour's Motor, 1860. English patent No. 1581 |

|---|

|

|

| George Hayes (millwright), 1861 British patent No. 1112. Dircks (1870), p. 257. |

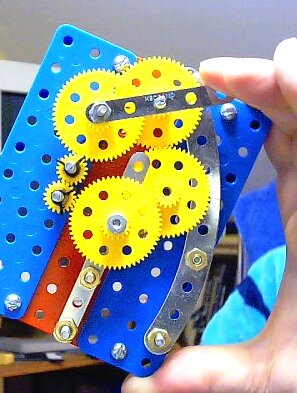

Construction set model of Hayes' device |

|---|

The inventor says that "the static pressure of a weight or weights applied to an axle of spindle is caused constantly to preponderate upon one and the same side of another axle, which is in gear by means of spur wheels with the axle or spindle to be turned, and has thus a constant tendency to assist the said last-named axle or shaft to turn in the direction required, whereby an additional power, in proportion to the weight used, is gained."

The helpful arrows show the result when the crank is turned clockwise. What would happen if the machine were operated in reverse? This is one of the most original ideas in the perpetual motion literature. Too bad it's entirely ineffective.

It's hard to resist thinking that this device is some clever engineer's deliberate joke, designed to challenge people to figure out why it won't work as claimed.

Some may think the defect in this device is that "floating" gear that has no axle. They think it will simply roll or fall out of place. That's not necessarily so. This construction-set model has the floating gear constrained by guides (the chrome-plated strips) to remain in one plane, but is completely free to move in that plane. The upper lever may be lifted and that floating gear may be easily slid out and removed entirely. So long as one keeps load on the upper right gear (supplied here by a finger, but Hayes suggested weights on its axle), the floating gear remains in place, and the gear train may be rotated in either direction. The minimum angle between the axles of the floating gear and its neighbors must be chosen relative to the angle of the individual gear teeth. This is something they don't tell you in engineering mechanics courses, probably because such floating gears have no conceivable use. [Some reader will probably inform me of a practical use.]

U. S. patents may be searched online at the U. S. Patent Office. It's sometimes slow and frustrating, though. A search for "perpetual motion" won't get you very many hits, for savvy patent lawyers know enough to avoid that term in a patent application. But once in a while a patent will declare that it is not perpetual motion. The examples may give you ideas for search words.

European and worldwide patents may be searched at the European Patent Office.